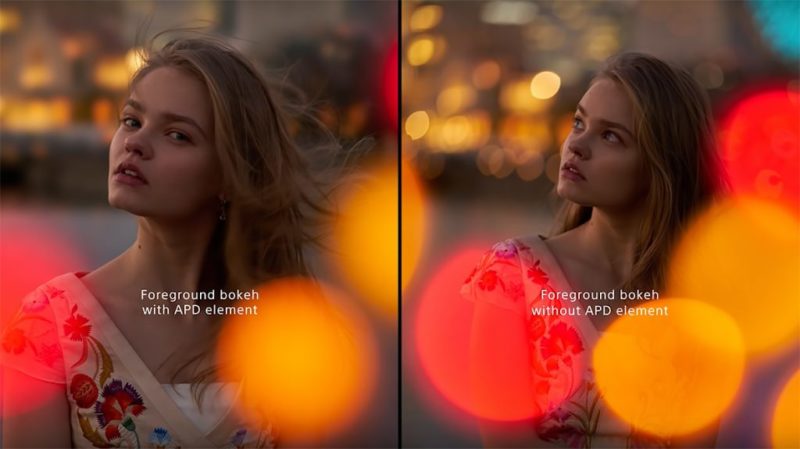

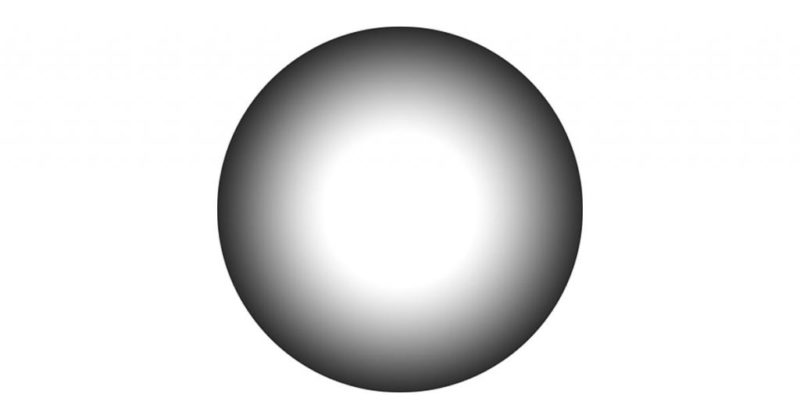

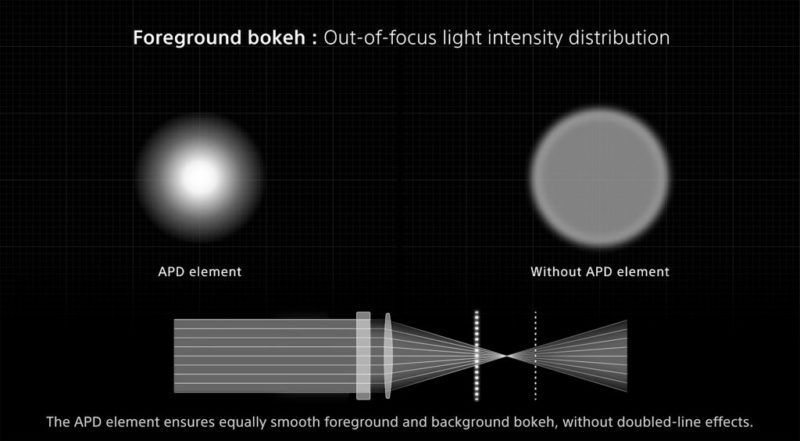

An apodization filter is a graduated neutral density filter that sits inside the back of a lens, and helps to smooth out the transitions in out-of-focus highlights or “bokeh balls”. Whilst the effect is most obviously seen in these highlight areas, as you can see from the Sony example below, the filter also causes a general smoothing of all OOF background areas. In short, if you want awesome, creamy looking bokeh, a lens with an APD filter is the way to go.

So why haven’t we seen more of these lenses then, if they produce such a generally desirable result? I mean, everyone want’s creamy bokeh, right?

An apodization (APD) filter isn’t without its complications. Firstly, for something that is essentially a radial ND filter, manufacturers like to charge a good chunk more change for an APD equipped lens. The second issue is that it causes a pretty severe loss of light, and it’s not something you can turn on and off, so this can be a big concern for some people.

For example, the Sony G Master 100mm STF lens is an f/2.8 lens in terms of the physical size of its aperture, but it actually behaves like an f/5.6 lens in terms of how much light it can let through to the sensor. That’s a considerable loss of light! One might term an f/2.8 lens a good lens for low-light situations, but you would never say the same thing of an f/5.6 lens. Things are improving these days because high ISO image quality has improved vastly in recent years, but the simple fact that there is so much permanent light loss inside the lens keeps it as a pretty specialist item in most people’s eyes.

Another issue that used to plague lenses with APD filters is problems with autofocus. Phase detect AF systems were confused by inconsistent light levels derived by the graduated filter, so the first APD-equipped lenses were manual focus only. Today’s much more advanced AF systems no longer struggle, but it was a significant early factor in the slow adoption of the technology.