You’ve been warned!

In an earlier post here on Shutter Muse, I revealed how seductive the call of film photography can be, and that even the oldest, most basic cameras can present a rewarding learning curve. I’m writing this little update several months later to say that first spark of curiosity has led to an ongoing shift in my photographic processes and priorities.

If and when you dare to explore the world of film photography, you might find yourself ignoring the latest rumours of gee-whiz technology waiting to be announced, and instead find the dark, dusty corners of flea markets, swap meets, garage and estate sales suddenly have an inexplicable allure.

Rolleiflex 3.5F

Rather than waiting and wondering what the big manufacturers will hand you next, my journey with film photography has become a choose your own adventure story; one filled with twists and turns as I unpack and reverse engineer decades of then-cutting-edge technology.

My own collection continues to grow, with both well-researched acquisitions like the Rolleiflex 3.5F TLR and donated curiosities like the Kodak Pony II and Kodak Brownie Reflex TLR. One camera, a Soviet-made Zenit 12XP, even made its way to me from a Shuttermuse reader in Germany. Thanks, Miroslav!

Kodak Pony II 35mm camera, complete with handy guides.

Out shooting with one film camera or another, I’ve had numerous bystanders come up and strike up a conversation. On several of these occasions, the question eventually emerged, “Why don’t you shoot digital?”. But this needn’t be an either/or proposition. Rather than trying to establish that they don’t make ‘em like they used to (although, for both better and worse, they really don’t!), my intent with this adventure is to go with the flow and see what lessons I can apply in both the digital and film realms.

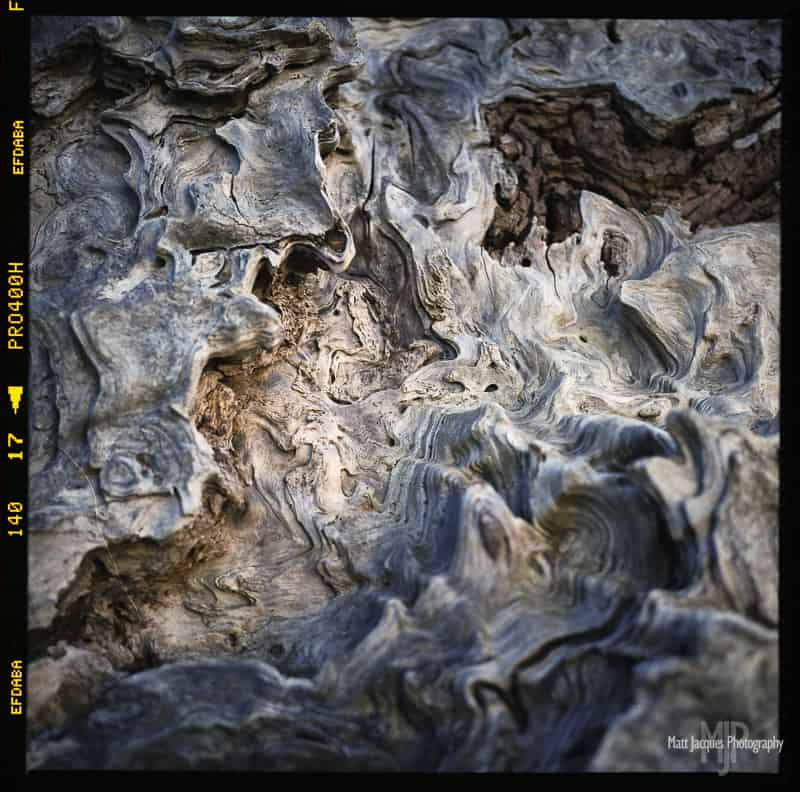

Driftwood details, Kitsilano Beach, Vancouver. Shot with Rolleiflex 3.5F on Fuji Pro400H film.

Part of that adventure has now included some highly enjoyable darkroom time. With the guidance of an excellent instructor at Emily Carr University, dodging and burning suddenly became much more than bizarre names for post-processing actions. The more time I spent in the darkroom, the more I realized as well what a completely irrelevant question it is whether an image has been ‘photoshopped’ or not. As image-makers, professional photographers have always used whatever tools are available to them, to shape images into an expression that best matches what they had visualized and now wish to communicate. Being a film photographer doesn’t mean being a ‘purist’, if that means no cropping, tweaking or adjustments.

Midtown Manhattan. Shot with Rolleiflex 3.5F on Kodak Tri-X 400 film.

Another endearing aspect of my film cameras is that they seem to have stories of their own waiting to be told. It’s easy to leave the utilitarian DSLR in it’s drawer until the next assignment, but a film camera gets upset when neglected and left on the shelf for too long. I swear, some even beg to be taken for walks! Each camera has its own characteristic ‘language’ that you must learn, in order to communicate effectively with it, as well as a unique ‘voice’ that comes through in the final image. It’s a beautiful grammar of ancient optics, exposure-setting controls and emulsion characteristics at play with the frequently perplexing mechanical idiosyncrasies of that particular light-tight box.

I’m off now, to take my Rollei for another little stroll and spend some more time learning its language!

Thanks for another great post Matt!