NOTE: As you scroll through these aerial photography tips you’re going to see that I put a TON of time into this for you guys. To show your appreciation, it would really help me out if you used the sharing buttons to help spread the knowledge around! Make sure you read all the way to get your FREE preflight aerial photography checklist at the end!

I recently had the pleasure of taking an aerial photography flight with Sea To Sky Air above Whistler and Squamish in British Columbia. The Sea To Sky corridor has been my home for over ten years and it was an incredible experience to see it from this unique vantage point. Since I took their Coast Mountain Photo Epic flight which is designed with photographers in mind, I was able to plan my preferred route for the 75 minute flight to make sure I covered some specific areas at the right time.

Whenever I do these kinds of interesting photo projects I like to use the opportunity to create some new content for this site, so today I’ve got all the tips you need to get epic aerial photos when you fly. Perhaps it will even inspire you to get up in a sky for your very first aerial photo shoot!

In this guide, you’re going to learn everything you need to know about capturing great aerial images from either an airplane or a helicopter. I’ll teach you what kind of settings you’ll require to get sharp images, which lenses will work the best and even discuss the relative merits of using either a plane or a helicopter.

4k Timelapse + Slideshow from My Flight

When I set out to do this aerial shoot I knew I was going to be creating a tutorial for the site so I wanted to do something a little different to make this the coolest tutorial of its kind on the web! Throughout this post you’ll see some of the photos I took during my flight, but I’ve also put together this timelapse of the flight that shows me shooting the images. If you’ve got the internet bandwidth, I’d recommend opening it up on YouTube and watching it full screen in 4K resolution! Please give it a share and thumbs up if you like it 🙂

To pre-empt the question, the timelapse was shot using a GoPro Hero 4 Black, with the timelapse mode set to take one photo every second. The battery just lasted the whole 75 minute duration of the flight. The 4,500 photos were then combined together into the timelapse using the GoPro Studio software and exported in the highest resolution possible with GoPro’s CineForm codec. I then took that plain timelapse and threw it into Final Cut Pro X, where I added the additional slideshow images and set it to music which was licensed from Triple Scoop Music.

I’m pretty pleased with how it turned out! Now, on with the rest of the tutorial and my aerial photography tips for you.

1 – Think About The Time of Day

When you book your flight you’ll want to take some time to consider the time of day and angle of the sun. Just like regular landscape photography at ground level, the light is going to be softer, and create more contrast at the beginning and end of the day. Avoid midday flights at all costs! Thankfully for my flight, Sea To Sky Air let me choose the perfect time in the late afternoon. Most sightseeing operations will have to have their planes back on the ground a certain number of minutes before sunset in order to comply with regulations. If your chosen operator has indicated that you can pick a specific time for your flight, you’ll want to find out that additional information as well to assist your planning.

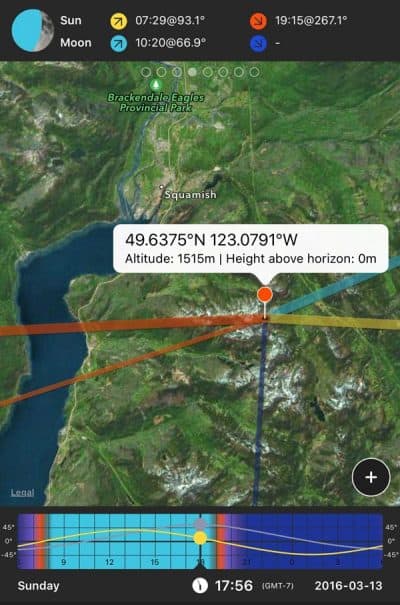

Of course the time of day doesn’t just effect the softness of the light, it also changes the direction. To accurately plan a photo flight you should have some idea of exactly what subjects you want to photograph so that you can work out which sun angle will make them look the best. I use the iOS app Photopills, to see the direction of sunlight at any location on any date and any time. For this particualr flight over Whistler and Squamish, my main targets were two prominent peaks: Black Tusk and Sky Pilot. Whilst an early morning flight can also produce great light for photography, using the app and my existing knowledge of these two locations, I determined that an evening flight would produce the most desirable results. Andorid users can get a similar experience from an app called The Photographers Ephemeris.

2 – Use a Safety Tether for Your Camera

This is another tip that is relevant to both photography from an airplane and a helicopter. It’s very important that nothing can fall from the aircraft so whenever you’re sticking camera equipment out of an open aircraft door or window, it needs to be securely attached to you. A neck strap is the obvious first precaution but it can limit your movement. Whilst it’s always best to have a clear view through your camera’s viewfinder to properly compose your shot, there are certain angles you may want to achieve where there isn’t possible, particularly if you are wearing a restrictive seatbelt, or full harness if you are “doors off” in a heli. You might find yourself wanting to use a rotating LCD screen on your camera to compose a shot at arms length, and this is where a regular neck strap can cause problems.

My favourite solution to this problem is to use a little strap called the Leash, from Peak Design. It’s actually something I carry around in my camera bag all the time, and I often tether my camera to me when I’m leaning over the edge of a cliff, bridge, waterfall or chairlift. The Leash is a designed to be an ultralight shoulder strap, but it also has the added ability to create a closed safety loop around something. You can strap it round your wrist, through a belt loop on your pants, to the shoulder strap of a backpack or in this case, to something inside the plane. It uses the tried and tested Peak Design quick release system so you can remove it in a flash, and I actually use it as my day-today camera strap because I love it’s multipurpose design. (Check out a full review of the Peak Design Leash here)

Obviously you would still do some severe damage to your camera if you dropped it, because the wind speed is high and would whip your camera against the side of the aircraft pretty hard, but at least it wouldn’t fall. For added security, I team my Leash strap with the Clutch hand strap from Peak Design – they make the perfect paring. The Clutch is a simple hand strap that makes it hard to drop your camera in the first place, so hopefully the Leash is just there as a backup. With the Clutch done up tightly, you can actually release your finger grip on the camera and it’ll stay firmly glued to your hand. It’s also great because it means you won’t drop your camera on any of the aircraft controls if you are in a tight front seat. I love these things, and I have one on all my DSLRs.

If you are doing a lot of aerial work and want an even more robust tethering solution then you can check out my guide to creating the ultimate camera tether using climbing equipment.

3 – Ditch the Lens Hood

You’ll find that many aerial tour companies will ask you to do this anyway, but even if they don’t, I think it’s a good idea. Lens hoods can be insecure and you don’t want it flying off your camera and potentially causing damage to the aircraft, or hurting someone on the ground. If you’re shooting from a high wing aircraft, you’ve got yourself a pretty good shade anyway! If you do find yourself with a lens flare issue then a well positioned hand can usually solve the problem in a pinch.

4 – Don’t Forget Your Gloves

You might have noticed in the photo at the top of the post that I am wearing gloves while I’m shooting. Whether this is absolutely necessary will depend on your location, but air temperatures will be dramatically lower at altitude and even in warm climates most people will find it more comfortable to protect their hands from the cold air that’s rushing past.

I have previously written an extensive guide to the best photography gloves on this website so you might want to check it out to see all of the options. For aerial photography in most locations, a liner style glove is going to be sufficient, and the various versions from The Heat Company would be my pick.

The only time when I would also bring a thicker pair of gloves is if I am shooting from a helicopter with the whole door removed. In a heli this can make for a great photography platform, but it’s far from a comfortable experience as you are exposed to the cold, rushing air for the duration of the flight. In this case, I might opt for a thicker glove like the Shell Mitt from The Heat Company, which I would then combine with one of their thinner liner. Simply zip open the mitt when it’s time to shoot!

In this “doors off” helicopter situation, I also highly recommend bringing a face mask or balaclava to protect your face.

5 – Choosing the Right Lens

This is a pretty significant section because it can really make and break the kind of photos you get from your flight. I’m going to discuss the lenses that I have found useful over the years, and also the exact ones that I used for the photos on this particular flight with Sea To Sky Air. If you don’t have the exact lens that I mention, don’t panic! The important thing is to have something close, in terms of focal range, but also remember that you can rent lenses for a fraction of the cost of your flight. If you are spending hundreds of dollars on the flight, it might also be a good opportunity to rent the perfect lens for the job from someone like Borrowlenses.com or LensRentals.com.

My first recommendation is to use a zoom lens so that you can cover multiple focal lengths very quickly. When you’re flying past your subject and the light is just right, things happen pretty quickly. That ability to get several different looking photos within a second, by using a zoom lens, is absolutely key to maximizing your flight time. The word “zoom” used to be a dirty word in terms of quality, but that’s not the case these days. There are some truly wonderful zoom lenses out there and I make use of them on a daily basis for my photography work.

Not only will a zoom lens give you different images in a single pass, but it’s also a much safer option as it’ll prevent you from dropping a lens in the confined space of the cockpit. On helicopter flights with the doors off, you won’t want to change a lens at all! If that’s the kind of flight you’re on, you’ll need to bring multiple cameras if you want to use multiple lenses. Again, you can always rent an extra camera for a very small price compared to the cost of your flight.

For general aerial landscape photography, a zoom lens that roughly covers the 24-105mm focal range is the ideal lens. I say “roughly”, because a 24-70mm will also be a very good option. On this particular flight that I took, my Canon 24-70 f/2.8 L II was used for 90% of the images. I used a Canon 8-15mm f/4 L Fisheye for the interior shots that include the pilot, I used the Canon 11-24 f/4 L for a couple of shots that included the exterior of the plane, and I also used my Canon 100-400 f/4.5-5.6 L IS II for the image of the fiery orange sky on the horizon.

The 24-70mm did the majority of the work, and I would have still been very happy with my images had this been the only lens I had available to me. That said, if you own additional lenses as I do, it makes sense to bring a couple along for special circumstances. If you have a 16-35mm lens then this is great for interior images, as is a fisheye lens.

6 – Choosing the Right Camera

When it comes to camera choice for a flight like this, there’s two main things to consider: Resolution, and high ISO performance. There isn’t really a minimum number of megapixels you should have, but when it comes to aerial photography I say the more the merrier. More megapixels will give you must more fine detail which both great for large prints, but also gives you “spare” resolution that allows you to crop your image and still maintain a good final image size. With the movements of the plane and the constantly changing orientation, it can be tough to nail the perfect composition if it’s your first time in the air. Things just seem to happen so fast! If you have a lots of megapixels, you can afford to shoot your compositions a little bit looser, and then rotate and crop the a little as necessary when you get them onto your computer.

The second important consideration is the camera’s high ISO performance. In fact, I’d probably rate this as more important than the megapixel count! Light levels are going to be fairly low if you’re shooting at either extremity of the day. When you combine this with a necessity for a decent depth of field in your landscape shot, and the requirement for a fast enough shutter speed to prevent the plane’s movement from blurring your photo, you quickly end up pushing your camera’s ISO fairly high. When you push a camera’s ISO higher and higher, the images will get softer and softer, and more noise will begin to creep into them. Full frame cameras always have less noise (i.e. better high ISO performance) than their crop sensor equivalent from a similar time period, so you’d do well to get your hands on a recently released full frame camera if you really want to maximize your results. Confidence in the high ISO capability of your camera will allow you to shoot with a nice safety buffer on your shutter speed to make sure you don’t see any blurring, even when zooming in to use longer focal lengths. If you can confidently set your camera to something like ISO2000 and still get great looking shots, you’ll probably be fine, but there’s no harm in being able to go even higher.

If you’re hoping to use a pocket-sized point and shoot camera then I think you might be disappointed with the results. Photos would likely be fine for small 4×6 prints and digital usage on somewhere like Facebook, but I can’t help thinking that if you’re the kind of person who has already made it this far down my rather lengthly list of aerial photography tips, you’re probably someone who’s probably looking for something a little bit better than just passable. Point and shoot cameras have very small sensors and this means that their high ISO performance is terrible in comparison to even a cheap DSLR. In some situations it might not be so noticeable to you, but I’m telling you right now than low light aerial photography is a situation that would really reveal the weaknesses of these kinds of cameras. A DSLR or a mirrorless camera with a sensor of at least APS-C size should be considered mandatory if you’re really looking to get the best from your photo flight.

Additional reading: Understanding ISO and Understanding the Exposure Triangle.

7 – Selecting the Best Camera Settings

With aerial photography, your number one priority in the exposure triangle (shutter speed, aperture, ISO) is going to be shutter speed unless you are in a helicopter in a hover. When you’re in forward flight in a helicopter, or a plane, you need to select a shutter speed that is going to freeze the motion and deliver a nice sharp image. From my experience, I can tell you that you should be using a minimum of 1/640 second and preferably 1/1000 or higher for longer focal lengths. Remember that the longer your focal length, the faster the shutter speed will need to be to get a sharp image. So a photo at 24mm might work at 1/640, but if you zoom in to 100mm or more, it’s going to be a bit blurry. You’ll notice in the photo below that as I zoomed to 70mm for that shot, I went up to 1/1600 of a second to be safe. Further down the page I used my 100-400mm zoom at about 250mm and for that shot I went up to 1/2000 of a second.

With shutter speed being so important in this situation, I don’t recommend using fully automatic exposure on your camera because you’ll have no control over what the camera is choosing in shutter speed terms. If you’re not comfortable with manual exposure, then you’re best option is to use shutter speed priority mode, indicated by a TV on Canon cameras and an S on Nikon and other brands. In shutter speed priority, you will dictate the shutter speed, and your camera will determine which aperture will be needed to go with that and still achieve a correct exposure.

Whilst you hand off the selection of the aperture to your camera in this situation, you still want to pay close attention to what it is selecting, because this will determine the depth of field in your images. My advice is to have an aperture of between f/5 and f/11. If you see that with your shutter speed set to something like 1/1000, your camera is choosing an aperture that is wider than this, like f/2.8, then you need to increase your ISO to compensate and this will allow your camera to stop the aperture down a bit more and gain a deeper depth of field.

As well as setting your shutter speed, you should also set your autofocus to “one shot” mode. There’s no need to perform any sort of continuous AF tracking while your’re shooting because your subject will be remaining roughly the same distance from the camera.

Additional Reading: Understanding Aperture and Understanding Shutter Speed.

8 – Minimizing Vibrations

Light aircraft and helicopters vibrate a lot when they’re flying, and it can cause your photos to be blurry even if you have selected the right settings after reading section #7 above. If you’re using a lens that has image stabilization, by all means use it – this definitely helps a lot! The key to minimizing the issue is to isolate yourself from the aircraft as much as possible. If you’re shooting through an open window, don’t be tempted to rest your camera on the window sill, or even lean on it with your forearms. Poke your lens through the window without touching any part of the side of the plane. This keeps your main contact point with the aircraft right where you are sitting, and any vibrations can then be dampened by your torso and arms before they reach your camera. If you are shooting though a closed window, make sure the front of the lens doesn’t touch it at all.

9 – What to Do with Windows

Ideally you’re going to want to find a sightseeing service provider that has an aircraft with a window that opens wide enough for you to shoot from. Take another look at the top image in this post and you’ll see how wide the window was on the Cessna that I used. Most light aircraft and helicopters have perspex windows, not glass, and this plastic will cause a colour cast on your photos if you have to shoot through it. I personally would not take a flight for photography specific purposes that forced me to shoot through a window, I know I’m just not going to get accurate colours or the sharpest images. Having said that, I have taken several flights where the primary purpose was transportation, but I still wanted to get a few photos on the way. These kinds of flights aren’t quite so geared up for photography so they might not have windows that open. In this situation the first thing to remember is that you want to put the lens as close to parallel with the window pane as possible, if you shoot at an angle through perspex, it will cause major distortion and softening of the image. Also try to avoid bulbous dome-shaped windows which will also distort heavily.

The next thing you need to do is minimize reflections on the window. The number one thing that is going to be reflected in the window is you! If you wear a bright red t-shirt, you’re going to have a bad time of it and there will be a red colour cast on all your photos. Try and wear neutral dark grey or black. You can further decrease reflections on the window by cupping your hand around the front of the lens in a similar fashion to a lens hood. Then press your hand up against the window to prevent stray light getting in between the lens and the window. If you want to get really serious about it, there’s a product called the Lenskirt, which is designed exactly for this purpose. It uses suction cups on the window to create a black curtain for your lens to poke through. I have one myself and have used it for taking photos through the window of airliners.

Like I said, for great photography you’re going to want to find an airplane or helicopter company that will let you shoot through an open window, but if all else fails, or you just happen to find yourself on an plane for another purpose, keep these tips in mind.

10 – Shoot Your Pilot and Passengers!

Ok, that sounds bad. What I mean is that there will undoubtedly be moments between shooting interesting things outside the window. This might be a once in a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for you so I’d always recommend taking a few additional photos of the other people that were involved in the experience. When you look back on your flight in a few years time you’ll be glad that you took a little time to do this because it will help you remember the adventure as a whole, and not just a series of photos. I always approach every photographic experience as if I was shooting for one of my editorial clients, and I try and get a series of photos that tell the full story. One of these dramatic landscape photos on its own might be nice, but it’s hard to get the full picture of your experience from it. When you combine it with these extra images, I think you’ll agree that you start to get a real feel for my experience on this flight!

Now that I’ve said that, I should also mention that using a flash might be necessary to get some shots of this kind. When it’s very bright outside, and relatively dark inside the plane, it’s hard to pick out the details of the plane’s instrumentation unless you light them with a flash. If you were to expose your shot so that you can see the interior of the plane, you would normally blow out the highlights in the landscape outside the plane. The flash allows you to correctly expose for the brightness outside, and then fill in the darkness inside the plane with the flash burst – this technique is called fill flash.

With such vastly differing lighting levels between the interior and the exterior of the plane, it can also be a tricky situation for your camera’s automatic flash meter to gauge the settings correctly. Some practice with either manual flash usage, or using the flash exposure compensation dial (FE) will be beneficial in this situation so that you can dial in the correct brightness for the plane’s interior. If that stuff is new to your but you’re planning a flight some time in advance, I would definitely recommend practicing this technique before you get in the air. You can always recreate a similar situation by using a car’s interior for practice!

11 – Adjust Your Altitude

When you first get up in the air, everything is going to look amazing to you, but there are a number of ways you can change the look of your final images. The biggest one of these is to ask your pilot to adjust your altitude. Just changing things a thousand feet can have a dramatic effect on the composition of your images if you are flying close to protruding landscapes and not just shooting ground-level patterns. If you climb higher, much more will be revealed in the background of your images. If you have a subject in your foreground that you want to isolate from a surrounding landscape, a lower altitude is better for this.

To demonstrate this point, I asked my pilot to fly two identical headings along a ridge line with the stunning Sky Pilot mountain in Squamish as my subject. Sky Pilot has its peak at 2,031 m (6,663 ft). The first pass was done at roughly the same heigh as the mountain, and the second pass on the exact same heading was done a few hundred feet higher that the peak. Look at the difference this made to the composition of this shot! The lower altitude does a better job of isolating the mountain as a singular subject, whilst the second one puts it much more in its place within the Coast Mountain range since you can see more of the mountains beyond it. I wouldn’t not necessarily say that one shot is better than the other, they key is just to remember that a relatively small altitude adjustment can make a big difference. Make sure you talk this through with your pilot before you take off, and be aware that comfortably gaining and losing altitude in small unpressurized aircraft can take a few minutes so factor this into your flight plan.

12 – Yaw and Roll Control

I wanted to include this diagram because I think it’s a good idea to know how to correctly communicate with your pilot. In a high winged aircraft like a Cessna, it might seem like a real problem to have the wing and the wing strut right outside your window, but actually this is a problem that’s solved relatively easy when you have good communication with your pilot. As you approach your intended photographic subject, the pilot can yaw the plane to the left (assuming you are on the right), and this will move the strut out of your way. You can also roll it slightly to the left which will bring the wing tip up and usually give you plenty of viewing space to get a clear shot. Until I went on this particular flight, I’d actually only shot from a helicopter before, but I was pleasantly surprised how easy it was to get a clear view from the side of the Cessna as well.

Make sure you discuss this with the pilot before you take off, and be aware that these adjustments to the aircraft will ultimately result in a change of direction if they are held for a long time so any request to perform them should be left right until the best shot is approaching.

13 – Don’t Forget the Plane!

This tip is something of an extension to #10 where I underlined the importance of capturing the whole experience of your adventure. Even if you’re buzzing with excitement before your flight, or pumped up on adrenaline afterwards, don’t forget to grab a few photos of the wonderful machine that took you up there!

14 – Shoot In Portrait and Landscape Orientations

It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement while you’re flying and forget to rotate your camera to shoot some images in a portrait (vertical) orientation. Many landscapes do lend themselves better to the landscape (horizontal) orientation, but there’s often great shots to be had when the camera is rotated 90 degrees. By having some variation in your resulting images, you’ll give yourself much more choice if you want to create some prints from the images, and the same thing applies if you submit your photos to a stock photo agency. Heck, portrait orientation images even look better on Instagram than landscape orientation so even if it’s just for that reason, it’s worth mixing things up a little! When i’m flying into the perfect photo spot and lining up a shot, I’m usually thinking two or three seconds ahead of myself so that I have already pictured the perfect portrait composition for a shot that I’m currently shooting in landscape. I’ll try and capture everything twice to give myself as many options as possible when it comes to satisfying my needs, and those of my clients.

15 – Check Your Cards and Batteries

The night before you head out for your flight, make sure you put your batteries on charge so you can start your flight at 100%. You should also make sure you have an empty memory card in your camera, and ensure that its size is going to be able to more than suit your needs. There’s nothing worse than missing the shot because you are too busy fumbling with changing out a battery or a memory card! If you’re on a tight schedule, it might not be possible to fly around again and take another look at things!

16 – Don’t Pray For Great Weather

Contrary to popular belief, it’s actually best not to have perfect weather on a flightseeing photo tour. If you can afford to be flexible in when you book your flight, it’s best to keep a close eye on the forecast and try and get a day that’s partly cloudy. Clouds add so much drama to a scene, and when they block sunlight from hitting the ground, or other areas of the landscape, they create contrast and contrast is the key to compelling imagery. Clouds create contrast for us on the ground, and also in the sky where you can see darker and lighter ares of cloud cover as the layers overlap. For this flight over Whistler and Squamish I studied the forecast and even called the shoot off on one day when the weather was too good. In the end my patience was rewarded with what I would consider to be perfect weather for this kind of photography.

The other benefit of varying cloud cover is that it will create something totally unique. On a bluebird day, the landscape is going to look just the same as any other bluebird day, but on a day with some clouds brewing, you’ll get contrast and dappled light across the landscape that’s almost guaranteed to never be the exact same again. If you plan on taking multiple flights in one location this is perfect because they’ll all be slightly different.

17 – Shoot in RAW

Does your camera shoot RAW images but you haven’t gotten around to trying it yet? Now isn’t really the time to go into a great RAW Vs. JPEG debate, both of them have their benefits and suit certain needs. Personally I’m always looking to extract the absolute highest quality images from my camera, and that’s what RAW photos are designed for so I use my cameras in this way every day. One of the best reasons to shoot RAW is that it gives you much more latitude for adjustment of your images on the computer, before the file starts to break down and reveal digital noise and artifacting. It’s always best to get your exposure correct when you shoot the photo, BUT, if you do happen to get something wrong (or your camera does), then a RAW photo is going to give you a better chance of rescuing a useable photo from the the mistake.

The reason I specifically mention this in relation to aerial photography is that exposure can be pretty tricky to deal with when you’re flying on a constantly varying heading in a small aircraft. One second you’ve got the sun behind you and everything looks great, then the next moment the sun is coming right at you and your camera is underexposing everything. As you’re happily clicking away and looking through the viewfinder, you might not notice that the exposure isn’t quite right anymore. We’re all human! Mistakes happen, and I can tell you from experience that this is exactly the kind of situation where it’s possible to get so caught up in the majesty of the moment, that you forget to check the results you’re getting. It would be a terrible thing to spend the money of a flight and then mess up the exposure on a great shot that could potentially have been rescued if yo’d been shooting in RAW.

Be aware, RAW photos are larger in their file sizes so you’ll need a larger capacity memory card than you might do if you usually shoot JPEGs. Keep tip #15 in mind!

18 – Use a Polarizer (Advanced)

A circular polarizer is, in my opinion, the single most powerful filter that a photographer can have in their kit. When used correctly, it cuts out reflected light and can have a dramatic effect on the colours within an image. If you’re shooting through a window, it can help to reduce glare on the glass or perspex, and if you’re shooting over water it will allow you to see right through the water in some cases, by neutralizing the sky’s reflection from the surface. As this side-by-side comparison shows you, they can produce dramatically different results, but they also have some downsides which are compounded in an aerial photography situation.

The first downside to a polarizer is that it cuts anywhere between 1 and 2 stops of light from entering the camera due to the darkness of the glass. If you’re already shooting in the low light of early morning or late evening, then light is precious, and you’ll have to compensate for that light loss in some way. We’ve discussed minimum shutter speeds in the earlier section so adjusting that isn’t really an option. You’re going to want to maintain a decent depth of field in your landscape shots, so that also means that opening up the aperture isn’t an ideal solution, either as this would lead to decreased depth of field. That leaves us with adjusting ISO. For this reason, I only recommend using a polarizer if you are shooting in very bright conditions, or you are utilizing a camera that gives you great confidence in its image quality in the ISO 1000-2000 range which is where I think you’ll find yourself. A full frame camera is a benefit due to their inherent better high ISO performance.

The second issue with polarizers is that they have a tendency to confuse the auto exposure sensors in cameras, causing them to either under, or over expose images when used in auto or semi-auto modes. For this reason, you either have to keep a very close eye on your resulting images whilst you’re shooting them, or you have to shoot in manual exposure mode. I recommend the later option.

The third issue with these filters is that to get the optimum result, the filter has to be rotated to the perfect position to cut out the reflected light. This position is different depending on what your angle is to the sun. On the ground, this isn’t much of a problem as you can simply turn the filter ring to the right spot and take your shot. Whilst you’re flying though, your angle to the sun is constantly changing, and that means that you have to constantly re-adjust the filter to find the perfect position again. If you’re also flipping your camera back and forth between horizontal and portrait orientation, that will require a further 90 degree rotation of the filter each time you do that. Now, imagine doing this in a fast fly-by of your subject whilst manually exposing, trying to keep the camera steady without leaning on the aircraft, battling a buffeting cold wind and still composing the shot correctly… You can see why I labelled this tip as advanced!

Whilst there are no negative effects to the colours of your image if you don’t adjust the polarizer all the time, you will still be losing that 1 to 2 stops of light which in turn will force you to pick an unnecessarily high ISO. In other words, only use a polarizer if you are going to commit to working with it correctly and constantly adjusting it to achieve the desired effect, otherwise you’ll be getting noisier images without any of the filter’s benefits.

I choose to work with Formatt Hitech Firecrest filters.

19 – Airplane or Helicopter for Aerial Photography?

As I mentioned earlier, this was actually my first aerial photo shoot from a plane rather than a helicopter, so I’m happy that I can now comment on this question from experience. I must admit that before taking this flight, I had assumed that it would be mush easier to shoot from a helicopter, but it turns out that’s not really the case.

I think the assumption is that with a helicopter, you can just hover in the right place and take a ton of photos to get the shot, but that’s not really the case. Helicopters use an enormous amount of fuel when they are hovering and unless you are paying for your flight by the amount of fuel used, the operator will almost certainly not let you simply hover in one spot for your photos. This means that generally speaking, your flight path is going to be pretty similar whether you’re flying in a helicopter or an airplane. One possible difference is the time it takes to change altitudes. I have found that you can increase and decrease altitude much quicker in a helicopter so that might be a consideration for you if you were looking to photograph one area from multiple heights in a short space of time.

Before talking to Sea to Sky Air I was also mistakenly under the impression that taking the door completely off would be much harder on a plane than a helicopter. I’ve often flown with the door off on a helicopter because they come off quite easily and it provides an uninterrupted view, albeit a very cold one. It turns out that you can take the door off a Cessna quite easily, but the benefit is somewhat negated by the landing gear that protrudes from the side of the aircraft. On a helicopter, you therefore have a clearer view looking straight down compared with a Cessna. If your photographic aim is to capture the patterns on the ground by looking straight down on them, it would prove easier from a helicopter, although also not impossible in a plane if you and your pilot are willing to roll the aircraft a bit more dramatically.

The biggest difference between these two modes of transport is probably the cost. It is considerably cheaper to fly in most small aircraft than it is in a helicopter. In my local area, a 20-minute helicopter tour costs $260 per person, but for just a few dollars more ($284/person) I could go on the 75-minute long Coat Mountain Photo Epic tour with Sea to Sky Air again. That’s a massive difference! The additional flight time was what allowed me to target two specific locations that were some distance apart, and take multiple photo passes at them.

If you can find a helicopter pilot with a smaller heli like a Robinson R22/R44 you can bring the cost down a bit compared with someone operating a Bell Jetranger or Eurocopter AS355 “Twin Squirrel”, but it’s still not going to compete with someone flying you in a small plane like a Cessna.

Incidentally, if you get into picking specific helicopters, the larger Jetrangers and Eurocopters can bring the price down on a per person basis for avid photographers because you can sit 3 people on one side with the doors off. One in the front, one sitting on the floor in the back and one sitting on the seat in the back. With a Robinson R44 the back is too small to have two people sit sideways on one side, so whilst the hourly cost is less, it might be more cost efficient in the larger helis if you have three people. Note that local air regulations may prevent any of these setups, so you should always discuss this before booking.

One more thing to bear in mind is that the rear seat in a Cessna likely won’t have an opening window, so this makes it much less useable for an avid photographer, whereas many helicopters will be able to accommodate two photographers on one side with both windows in the front and back seats. It may go some way to offsetting the vast plane/heli cost difference if you have a buddy who wants equal photographic opportunities, but it’s still going to be more expensive.

Hopefully these thoughts make your decision a bit clearer. I, for one, was very impressed by the effectiveness and the cost-efficiency of using a small plane, and I’ll definitely be looking to use one again in the future wherever I can!

FREE Preflight Checklist!

- Things to remember to take with you before you go to the airport.

- Things to remember during your flight.

Run through the first section before you leave your house to make sure you’ve got everything, and run through the second section just before you take off, while the pilot is doing his checks! That way you’ll have everything prepared, and have your camera all set up and ready to go.

Pin The Post

I’ve put an incredible amount of time into creating this post, if you use Pinterest, it would be a great help to me if you shared it using the graphic below.

Thanks for the post Dan!

In point 3, you advocate not using a lens hood? Why not use the ubiquitous ‘gaffer-tape’, and fix it on securely with that? Depending on conditions, I’d rather use a hood than a polarizing filter, as just about everything can be tweaked in post-production. Using a hand to shade a lens takes one off the camera and, as you need to have a very steady camera, I don’t see that as a good option at all.

You also mention ‘depth-of-field’ being an issue; at the (safe) distances most images are going to be shot at (and thus focused at), d-o-f will not be the issue it is with terrestrial photography – i.e. you are highly unlikely to have a field of focus which will include very close objects, unless you have an adventurous (or stupid) pilot.

Something much more important I haven’t seen you mention is insurance; before any such venture, you should ensure that, unless you are just booking a regular ‘sight-seeing’ flight, the aeroplane/and or pilot is insured for commercial work, and that you and your equipment are covered on your own insurance policy.

Many thanks for joining the conversation, Michael! I’ll tackle your points in reverse order:

1. Insurance – I hadn’t thought about checking the pilot’s insurance for commercial usage. If anything should happen based on their action, it’s not clear to me how the passenger (you or me) would be liable, though? I guess it doesn’t hurt to ask this question, but this is a confusing topic! I have public liability insurance for my business, but you make a good point about checking with your own insurers that this kind of activity is covered from that perspective. I guess the reason I don’t mention that is because it’s kind of one of those things you’d end up having to mention in every article. A photographer should have insurance even if they are out wandering around on their own taking landscape images.

2. Whilst DOF isn’t the instantly perceivable issue that it often is on the ground at close distances, it’s all relative. Shooting a landscape photo on the ground at f/7.1 or f/9 would, by many, be considered to have a DOF that is too shallow for critical sharpness way off into the distance. Technically that doesn’t change when you get into the air, but people’s acceptable limits probably do adjust to the situation. I accidentally shot a couple of images at f/4 on this flight, and whilst they difference would be impossible to spot in a web article, or even at a full page print in a magazine, it’s noticeable at 100% and therefore would be noticeable in a large print. Not a ruined shot by any means, but one that I simply would have preferred to have more sharp details at the horizon.

3. Lens hoods mainly give you more contrast when the light comes from certain angles, it’s quite rare that it will prevent flare because the exact angle of the sun for that to occur is very small, and that’s going to be moving as you fly. I can definitely easily bump up contrast in a photo, but in a lot of situations it’s hard to recreate the effect of a polarizer, more so than any other filter because it’s actually blocking some light from being record in the image, and it doesn’t do it in a uniform way like an ND filter does. Some adjustments could be made, but the equivalent sky adjustment you see in my polarizer example would introduce huge amounts of noise to the photo if you were to try and make an adjustment of that magnitude in Lightroom. Then you would have to make many small localized brush adjustments all over the image to truly mimmic much of the effect. I’m not a fan of committing so much time to post processing, especially when it might degrade the image so much.

As always, enjoyed reading your article Dan.

Although I love shooting from a helicopter platform and have about 1500 hours logged in military helicopters, like you mentioned, they aren’t the easiest platforms to shoot from in a hoover.

A lot of jet powered helicopters have the engines right under the main rotor. In a hover, the exhaust is blown straight down in front of the camera causing distortions in images. I always requested my pilots to maintain a little forward airspeed and a slight decent which pushes the exhaust up and behind the bird.

Additionally, like you mentioned, a hoover is hard work for a helicopter. Not only does it burn a lot of fuel, it induces a lot of vibration into the aircraft and into images.

One other issue I always found to be a pain with any aircraft is getting rotor blades or wings in the photo during turns. It’s like the pilot can sense when you are about to take the money shot and starts his turn.

The way I resolve the turn issue is rather than turning towards the camera side of the aircraft, instruct the pilot to do a 270 degree turn in the opposite direction. That will insure level wings and rotors while taking photos.

Absolutely brilliant tips, Wes! Do you mind if I move some of them up into the main article in a “Reader’s Tips” section?

I love your article. I would like to stress of a few points though. In aerial drone cinematography your prowess is very vital. I have done aerial drone photography for some time. During this time I have understood that mastering the art is more vital than anything else. Patience is a key element when it comes to this. This is the most ideal way to master every tricks including hovering, the right flying height, the best weather, the ideal shutter speed, what type of camera to use, when to shoot against the window, and how to take the best angle shots without crashing.

Thanks for the thoughts Jon!

I was going to fly out this weekend or next with Harbour Air in Vancouver, but will have to get my rookie thoughts in perspective after reading your article (thankfully). I haven’t flown since 2004. Anything to expect on a Cessna for the first time not to mention shooting the pilot, passengers and landscape to boot? Great tips

Sorry it took me a while to respond to this! Did you make it out? To be honest, I think the article covers most things to expect, so I hope you didn’t have any surprises 🙂

Great Work! This is one of the finest aerial photo blog I have gone through. All the things are explained in detail for a safe photo session. I will definitely keep in mind for my next trip.

Thanks Ryan.

Fantastic article – I am hopefully (weather dependent!) doing my first air-air shoot in a Harvard at the weekend. Thanks for taking the time to share, it is really appreciated!

You’re very welcome! Good luck with your shoot. Gotta love the sound of a radial engine 🙂

I am flying in a chopper over the victoria falls and as it will be my first aerial photographic expedition .I required some preflight tips and have googled several websites but this is the only one which has helped me, well done!

That’s great to hear, John! How did the photos turn out?

You did a great job of explaining these cool aerial photography tips. I am still a newbie photographer and looking for more information about photography. I really like number 16 stating that we should not pray for a great weather. Flexibility and risk-taking are really at its best!

Glad you liked it 🙂

I definitely agree! Tips are very useful and detailed. I am a newbie and I have always been praying for a good weather in order to not lose or risk it. Is it advised to attach a tracker to it in case the weather gets unpredictably bad?

Attach a tracker to what? I’m not sure what you are talking about.

I had fun reading your article, It’s very well explained and informative.

Thanks Miranda! I love hearing that 🙂

This is more detailed tips and this will be very helpful to those beginner aerial photographer.Thumbs up Dan!

You’re welcome, Sarah!

Great article and nice shots, i’ll be waiting for your next article! I love reading it.

Thanks Ryan! I hope you follow one of our feeds or sign up to the newsletter then. These are the best way to make sure you don’t miss anything. Is there a topic you would like to know more about??

My husband initiated me to aerial photography a few years back, but you just made me realize how much newbies we really are :D. We’re still having problems with our management of vibrations for the most part, but our experience grows at every session!

I’m going to try your exact settings and see what kind of improvement it makes.

Thanks again!!

Jessica T, founder at Joystock.

You’re welcome, Jessica.

Very great tips, detailed and very informative, thanks a lot for this pal! you’re a total Pro!

You’re very welcome Ulrich! Thanks!

Hi Dan, This post is like an ariel photography guide. The effort you have added in getting this post completed is visible. Beautiful shots are truly inspiring to get into the ariel photography. Thank you for the neat, calm and informative post.

Thanks for the kind words Dennis! I’m glad you found it useful 🙂

Superb post. The information regarding the camera is just amazing. Aerial photography may not be possible for all but this post is so inspiring to be one. Thanks for sharing.

You’re welcome!

great article Dan, thanks for exhaustive tips 🙂 Do you have any experience in aerial shooting in cold weather? Particularly, i’m looking for good cover that would protect body and lens from low temperature breezing air. My pilot warned me that he witnessed the lens motor failure due to low temperature blowing air. I’ve tried Manfrotto e702 cover bit it does not serve for this purpose, it is to robust and made for stand, ie more static situations, just like most covers that can be found on market. Do you have suggestions for cover suitable for aerial shooting (for more ‘moving/dynamic’ situations)? thanks

Hi Goran,

It’s generally pretty cold in the air no matter what time of year it is. As you can see, I also shot over very cold and snowy places and temperatures outside the plane were well below zero Celsius. Personally I do not think this would ever be a problem with a decent camera and lens these days, but if you feel you must take such a precaution then my recommendation would be to use an elastic band and strap a couple of hand warmers to the lens, then put a normal rain cover over the whole thing. My rain cover recommendations are here: https://shuttermuse.com/best-camera-rain-covers/

For what its worth, I think this will cause you WAY more hassle than its worth, though. A rain cover will flap around violently in the wind and make it harder to see through the viewfinder.

If the pilot warned you about this then I guess he has seen it happen, but it’s not something I think it likely at all.

thanks for a great post

You’re welcome!

Hi Dan,

Great article! Any tips for aerial shots over the ocean – ie islands or whales, etc?

Specifically when some shots would be of the water and some mountians (i imagine you’ve done this seeing as where you’re based!).

I’d probably have two bodies – one w 24-70 and maybe 100-400 II – both canon.

thx!

Good question Morgan. Firstly you would definitely want to have a circular polarizer. I know I mention it as being a “pro level” tip in this article already, but it’s certainly worth getting to grips with that if you are over water. It will make a huge difference to the colour of the water.

I think you’re spot on with the lens choice too if you think you might see some whales. If it was general seascapes and waves breaking on beaches I would say you can manage with a 70-200, but if you think there might be some wildlife then a 100-400 is great. Just remember that you will need to set the shutter speed on that camera to something considerably higher than the one with the 24-70 as all the vibrations from the vehicle will be magnified by the zoom length. Given how important that is, I would run that camera in shutter priority.

You are probably going to want a polarizer on both lenses, too.

How often should residential windows be replaced?

Really indepth article great job.

Thanks, Luke!